Iran, Israel, the Persian Gulf, and the United States: A Conflict Resolution Perspective

By Simon Tanios

Abstract

Throughout history, various conflicts have shaken peace in the Middle East with a prevailing tense atmosphere in relations between different parties despite some periods of relatively eased tensions or even strategic alliances. Nowadays, political leaders in Iran considers the United States an arrogant superpower exploiting oppressed nations, while the current mainstream politics in the United States sees Iran as irresponsible supporting terrorism. In sync with this conflict dynamic, on one hand, the conflict between Iran and many Gulf countries delineates important ideological, geopolitical, military, and economic concerns, and on the other hand, the conflict between Iran and Israel takes a great geopolitical importance in a turbulent Middle East.

In this essay, we expose the main actors, attitudes, and behaviors conflicting in the Middle East region, particularly with regard to Iran, Israel, the Gulf countries, and the United States, describing the evolution of their relations, positions, and underlying interests and needs. Then, adopted from Galtung’s transcend theory for peace, we expose some measures that may be conducive to peace-making in the Middle East.

Keywords: Iran; Israel; Gulf countries; the United States; conflict resolution.

Introduction

Conflicts in the Middle East have become a recurring feature in international media coverage, academic literature, and global politics. The region hosts various forms of violence, as well as is surrounded by other long-term conflict zones. However, Middle East exceptionalism is used to delineate the region's resistance to “democracy” and backwardness in social development and respect for human rights.

Within this dynamic, various forms of conflicts shape the region, in particular the struggle between Sunnis and Shiites, the Arab and Persian Civilizations, the legitimacy of the State of Israel in the Muslim World, and the mutual animosity between Iran and the United States. Many incompatibilities seem to define ongoing conflicts, leading to numerous attitudinal and behavioral consequences. These complexities attributed to the conflicts have led to multiple forms of violence, and failures in peace-making processes for decades.

From the Origin of an Irreconcilable Sunni-Shiite Split: The Killing of Al Husayn

Among the 1.6 billion Muslims in the world, about 90 percent are Sunnis and 10 percent are Shiites (Pew Research Center, 2009). The history of the split, playing a major role in Middle East current conflicts, began after the death of the Prophet Muhammad in 632 AD. At that time, some believed that to be caliph, one needed to be a descendent of the Prophet Muhammad (these believers became known as Shiites, or “Shiaatu Ali” in Arabic meaning “Ali’s faction” relative to Ali Bin Abi Taleb, Muhammad’s cousin and son-in-law), while others believed that the choice of a person as Caliph should be based on his virtues without the need to be a descendant of Muhammad (these believers became known as Sunnis, or “Sunnat Al-Nabi” in Arabic meaning “the path of the Prophet”).

It is important to understand that the split on how to choose the next Caliph, turning into violence and the killing of the last descendant in blood of Prophet Muhammad, marks an irreconcilable conflict that lasts till now. Briefly, where the first three Caliphs (Abu Bakr, Umar, and Uthman) were not descendants of Prophet Muhamad, and after Caliph Uthman was killed, Ali, Muhammad’s cousin, proclaimed himself the fourth Caliph. A few years later, Ali was killed, and his son Hasan ruled for a short time before abdicating months later, when his brother Al Husayn demanded the throne. At that point, the struggle for control on leading the Muslim Caliphate became more violent, and a member of the dynasty of the third Caliph Uthman, Muhammad Yazid ibn Abi Sufyan, ruled the Caliphate. The latter, being not pleased by Al Husayn’s aspiration, sent a troop that killed Al Husayn and his companions in the famous city Karbalaa.

The killing of Al Husayn, the last direct male descendant of Prophet Muhammad, is the cornerstone of the Shiite narrative who viewed that they are deprived of leading the Muslim world, creating an unbridgeable split, if not animosity, between the Sunni and Shiite factions.

Arab-Persian Rivalry: Historical Overview

After nearly two decades from Prophet Muhammad’s death, in 651 AD, the four hundred years Persian Empire was occupied by Arab Sunni Muslims, and Persians, mostly Zoroastrians, were converted to Islam (Melamed, 2016). At that point, the power struggle over the rule of the Arabian Peninsula intensified, and the Sunni rule in Persia came to an end with the rise of the Shiite non-Arab dynasties that ruled between 1500 and 1979. When discussing the Arab-Persian rivalry, the year 1979, the date of the Islamic Revolution, is a milestone in Arab-Persian relations, since after then, Shiite clerics named Mullah, were raised to political power under the Country’s Supreme Leader then Imam Ayatullah Ruhullah Khoumaini. With the Shiite Mullah regime that established the Islamic Republic of Iran in 1979, the Sunni-Shiite and Arab-Persian rivalry have amplified, manifested in continuous conflicts, and different forms of violence between Arab Sunni states headed by the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and proxies, mainly Sunnis, and Iran and its proxies, mainly Shiites.

Iran-Israel Relations: from a “Strategic Alliance” to “Death to Israel”

The date of the Islamic revolution in Iran (1979) marks a shift in the country’s foreign policy in general and the Iranian-Israeli relations in particular. During the Shah regime, especially in the era of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi (1941–1979), Iran and Israel had close ties, even a strategic alliance (Menashri, 2013). Iran as a predominantly Shiite state, in a region predominantly Sunni and with a history rich in hostility to its Muslim neighbors, viewed Israel as a natural friend. On the other hand, Israel, searching for legitimacy in the Muslim world, viewed Iran as an ideal ally. Israel first Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion developed the concept of ‘the peripheral states’, arguing that Israel, as it had no relations with its immediate geographic neighbors, should seek the friendship of “the neighbors of the neighbor” as Iran and Turkey. These mutual interests established a strategic alliance between Iran and Israel before 1979 (Ibid).

However, with the ascendancy of the Islamic regime in Iran, this period of close ties came to an abrupt end. At the outset of the Islamic Revolution, the opponents of the Shah regime viewed the United States, and its great ally in the Middle East, Israel, by their support to maintain the Shah regime in power, as a system of oppression against the Muslim masses, opposing westernization efforts of the Western-backed Shah. These views became one of the most fundamental tenets of the revolution and were repeatedly stressed by Ayatollah Khoumaini before the revolution and have continued ever since. “Death to Israel” remained a central theme in Iran’s revolutionary politics, particularly after the Israeli disproportionate and violent response towards the Palestinian intifada that began in late 1987, resulting over 13 months in the killing of 332 Palestinians and 12 Israelis, and over six years of the Intifada, the killing of 1162 to 1204 Palestinians and 160 Israelis (Pearlman, 2011). Factors such as the ideological rejection of Zionism and the identification with the Palestinian cause from Iran’s perspective, the monopoly of nuclear weapons in the middle east region by Israel, coupled with pragmatic interests of States and global superpowers, have led to deep animosity between Iran and Israel.

Figure 1: A Palestinian boy and an Israeli tank amid the first Intifada ©Libcom

Iran, the United States, and the “Great Satan”

Going back in history, the United States was positively perceived in Iran. Iranians saw then the United States as a hedge against the imperial aspirations of Great Britain and the Soviet Union. Notably, at the end of World War I, United States President Woodrow Wilson supported self-determination for Persia at Versailles Peace Conference (Harrison, 2020). At the end of World War II, United States President Harry Truman put diplomatic pressure on the Soviet Union to withdraw its troops from northern Iran where they were supporting the Azeri and Kurdish separatist movements (Ibid).

However, this positive perception of the United States among Iranians started to change after the United states-backed overturning of Iranian Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh in 1953 who was viewed vulnerable to manipulation by Moscow amid the Cold War between the Soviet Union and the United States (Soltaninejad, 2015). After the coup, the United States supported the Shah of Iran to maintain power, fearing a potential takeover of the Soviet Union in Persia. Views among many opponents of the Shah were gaining power that the United States is enabling the Shah’s repression of Iranian people. The level of anger of the United States after the coup d’état that overthrew Mossadegh peaked amid the Islamic Revolution in 1979 where many Iranians depicted then the United States as “the Great Satan” (Harrison, 2020). The deaf of Washington to Iranian people self-determination demand was seen as a vital strategic interest amid the cold war with Moscow, particularly with the rise of Jamal Abdel Nasser to power in Egypt, who gained popularism in the Arab World notably for his anti-imperialism efforts leading to the British withdrawals from Egypt and nationalization of the Suez Canal, and was awarded the title of the Hero of the Soviet Union in 1964.

Figure 2: Iranian students come up US embassy in Tehran taking 52 Americans as hostages in 1979©revolution.shirazu.ac.ir

In 1979, Iranian students supporting the revolution took over the United States embassy in Tehran, where fifty-two American diplomats and citizens were held hostage for 444 days (Ibid). On the other hand, when Iraq, that was worried that the 1979 Iranian Revolution would lead Iraq's Shiite majority to rebel against the Baathist government, invaded Iran, the United States heavily supported Iraqi President Saddam Hussein with monetary supply, political influence, and intelligence on Iranian deployments gathered by American spy satellite (King, 2003). At that point, Iranian animosity towards the United States grew up, while Iranian view Washington as complicit in the Iraqi invasion of Iran.

Conflicts in Turbulent Middle East: Iran, Israel, the Gulf States, and the Axe of Resistance

In the previous paragraphs, we have exposed the main actors involved in the conflicts stemming from the Middle East, their incompatibilities, and the evolution of actors’ attitudes and behaviors depending on their interests and aspirations. We have also exposed how the conflicts were taking place in regional wars, political, financial, or logistical support to certain regimes, and diplomatic pressure, revolution, conspiracies, or coup d’état to overthrow others.

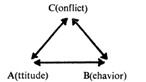

Figure 3: The conflict Triangle (adopted from J. Galtung Transcend Theory).

Built on that, we focus in paragraphs and seven on the main components shaping the conflicts nowadays, and the dynamics for regional hegemony in a geostrategic context.

For Iran and Israel, both countries began an early quest to acquire nuclear weapons, postulating a strategic threat, particularly after the Arab Spring. From the Israeli perspective, Iran’s increasing influence in the region through proxies could threaten Israel’s security, expansionary settlement plans, and military superiority in the region. By targeted military actions in Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, and strong lobbying power in Washington, Israel tends to maintain its geopolitical interest and the legitimacy of its state in the Muslim world. For this aim, Israel has even supported Sunni militants against Iran proxies during Syria’s War, in particular, Nusra Front, Al Qaeda offshoot, in south-western Syria in the Golan Heights, providing medical assistance, and logistical support to Nusra Front militants while fighting Iranian-backed Hezbollah in Syria and the Syrian regime (Maher, 2018).

In parallel, Iran’s growing regional activities fostered a new dynamic in the Middle East, where the Gulf countries became more dependent on the United States for preserving the Gulf security against the perceived Iranian threat, and by which we have seen an unprecedented rapprochement between the Gulf countries and Israel (Ibid). Undermining Iranian growing presence in the region intersects with the Interest of the Gulf regimes, Israel, and the United States. The Iranian-Saudi rivalry makes from Saudi Arabia the largest importer of Unites States weapons, with deals valuing 13 billion USD in the past five years (Armistrong, 2020).

On the other hand, Iran has established a powerful web of allies, notably Hezbollah in Lebanon, Assad regime in Syria, Hamas and the Palestinian Islamic Jihad in Palestine. In Lebanon, Iran backs up Hezbollah with thousands of rockets and financial aid, leading to political instability in the country. For instance, in 2005, the assassination of Lebanese Sunni Prime Minister Rafik Hariri, closed ally to Saudi Arabia, pointed to four Hezbollah commanders according to the Special Tribunal of Lebanon empowered by the United Nations Security Council. Hezbollah militants are actively involved in the war in Syria and Yemen, with militants’ training in countries as Iraq and Libya. Iranian support reaches as well the Assad regime in Syria and Houthis in Yemen’s war. Added to this, after the direct involvement of Iranian military force in the war in Syria and Yemen and the signature of the Iranian nuclear deal in 2015, the Irani-Arab struggle has even increased leading to an arm race in the middle east.

Iran-United States On-Going Conflict: the Cold War Doctrine

The United States has long operated with Iran with the strategic doctrine of the Cold War. With such a doctrine, the United States places troops in the region to deter Iran and impose economic sanctions to weaken Iran’s capabilities. On the other side, under the weight of the Arab Spring and the ensuing civil wars, Iran's presence through proxies in the region gives it a strategic power that has lacked during earlier periods of its history (Maher, 2018).

The toppling of Saddam Hussein handed Iran a strategic position by giving it a perfect opportunity to advance its strategic defense doctrines, giving Iran the ability to project power using its ties to the Shiite political leadership in Iraq. But it was the Arab Spring and the civil wars in Syria, Libya, and Yemen that enhanced Iran’s strategic strengths. Added to this, the mobilization of the majority of Shiite populations in Bahrain and Iraq, the two countries that for long were governed by minority Sunni governments, and the proxy war in Pakistan, negatively influence Saudi Arabia, and the United States interests in the region (Harrison, 2020).

On the opposite side, the United States government policies demonstrate the degree to which Iran is viewed as a primary threat to the United States' interests in the Middle East. President Donald Trump’s renunciation of the nuclear deal in 2018 could be considered ground zero (Ibid). This act was accompanied by a resumption of the United States sanctions, which a year later was followed by Iran’s provocative actions in the Persian Gulf. Since the mid of 2019, Iran and Iran-linked forces have attacked and seized commercial ships, destroyed some critical infrastructure in the Arab states of the Persian Gulf, conducted missile attacks on facilities used by U.S. military personnel in Iraq, and provided support to proxies in the middle east. After mapping these conflicts, we expose in the following paragraph some measures that may help in peace-making efforts in the region.

Figure 3: During the announcement of the Comprehensive Agreement on the Iranian Nuclear Program (Lausane, 2015) ©United States Department of State

Towards Conflict Resolution: Transcend Theory Perspective

According to Johan Galtung’s transcend theory (Galtung, 1965), any peacemaking efforts require in summary three steps:

- Mapping the Conflict and understanding what conflicting parties understand;

- Drawing a line between what is legitimate among demands and what is not;

- Bridging incompatibilities using creativity in wide sets of proposals.

Having mapped the conflicts given the limitations of this paper, we now move to a series of measures that may be adopted to bridge incompatibilities taken into consideration the legitimacy of demands, based on international laws, ethics, and human rights.

The measures below are adopted from Galtung’s work (Galtung, 2015), inspired by his prominent formula of peace:

Peace =(Equity*Empathy)/(Unreconciled trauma*Unresolved conflict)

where equal and mutual benefit, empathy, reconciliation of past trauma with compensation, and resolution of current conflicts are essential components for any peacemaking effort.

In summary, the Israeli part should:

- Downplay the claims of legitimacy and adopt a more realistic view of how Israel came into being. The state of Israel is a reality, but it is illegitimate to make the small land shared by Israelis and Palestinians the country of all Jews of the world.

- Downplay any future role in the Middle East based on efforts to divide the Arab states.

- Try to develop egalitarian relations with the Arab states, including respect for Islam religion.

- Give up the secure border idea and limit the Israeli state borders based on the 1967 agreement with adjustments.

In parallel, the Arab states, on top Palestine, should:

- Try to adopt a pragmatic and future-oriented position, while not focusing on the history of the past.

- Show a willingness to have direct negotiations immediately.

- Develop concrete images of an associative future, with a two-state solution.

- Think in terms of how territory could be made available to Palestinians and Israelis. Leasing lands from Jordan or Egypt is one proposed solution.

With regard to the United States peacemaking policies towards Iran, it should:

- Open high-level dialogues.

- pursue reconciliation resulting from Mossadegh coup d’état.

- Engage in cooperation in sectors of mutual benefits such as green energy.

- Avoid any attack against Iran.

Regarding the Gulf countries, they should:

- Do not interfere military in Arab countries, including in the war in Syria and Yemen.

- Support the establishment of a federation in Syria involving all different sects.

- Beware of splitting Syria to rule parts.

- Changing the discourse in the media that depicts Iran as the enemy of the Muslim Sunni world.

With regard to the United States peacemaking policies towards Syria, Iraq, and Yemen, it should:

- Work to give the right for the ethnic and religious groups for self-determination.

- Avoid any attack or invasion.

- Compensation and reconciliation for past harms and losses resulting from previous wars.

In parallel, Iran should:

- Stop financing militant groups in the Middle East.

- Show a willingness to direct negotiations with parties.

- Work on the democratization of its institutions.

- Develop a pragmatic approach in viewing the Israel State as a reality in the Middle East.

- A tit for tat approach may be used as a start point to build trust with conflicting parties.

Conclusion

In this paper, we explored from different perspectives the conflict involving Iran, Israel, the Persian Gulf, and the United States. We exposed the origin of the Sunni-Shiite split, the Arab-Persian rivalry, and the evolution of the relationship between the countries involved in the conflicts through history. Then, we explored the attitudes and behaviors of different parties, showing incompatibilities in interests and aspirations. We based on Galtung’s transcend theory of peace, and we proposed a set of measures that may help in peacemaking efforts in the Middle East. However, we completely understand the limitation of this paper, where books may be needed to map the ongoing conflicts and prescribe solutions that address the complex incompatibilities of conflicting parties.

References

Armistrong, M., 2020. The USA's Biggest Arms Export Partners. Statista, https://www.statista.com/chart/12205/the-usas-biggest-arms-export-partn…(Accessed on 27 June 2020).

Galtung, J., 1965. Institutionalized Conflict Resolution. Peace Research Institute.

Galtung, J., 2015. Peace Journalism and Reporting on the United Sates. Brown Journal of World Affairs.

Harrison, R., 2020. The U.S.-Iran Showdown: Clashing Strategic Universes Amid a Changing Region. Aljazeera Center for Studies.

Jordet, N., n.d. Explaining the Long-term Hostility between the United States and Iran: A Historical, Theoretical and Methodological Framework. The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy.

King, J., 2003. Arming Iraq and the Path to War. U.N. Observer & International Report.

Maher, N., 2018. Balancing deterrence: Iran-Israel relations in a turbulent Middle East. Review of Economics and Political Science, Emerald.

Melamed, A., 2016. Inside the Middle East.

Menashri, D., 2013. Iran, Israel and the Middle East Conflict. Routledge.

Pearlman, W., 2011. Violence, Nonviolence, and the Palestinian National Movement. Cambridge University Press.

Pew Research Center, 2009. Mapping the Global Muslim Population. http://www.pewforum.org/2009/10/07/mapping-the-global-muslim-population(Accessed on 21 June 2020).

Soltaninejad, M., 2015. Iran and the United States: A Conflict Resolution Perspective. Wiley Periodicals, Inc..